(Criminal) Justice Reform and Rule of Law: Strengthening Laws & Systems

An effective criminal justice and rule of law structure are the central elements of any national system of human rights protection. In many places in Africa, criminal justice systems remain rather fragile. Criminal justice and rule of law cannot be separated from democracy and human rights inasmuch as their effective implementation have become a barometer of democratic practices throughout the world.

AU Watch’s research shows that failure of governance institutions,at many levels, to design a suitable criminal justice policy, inability of many legislatures to appropriately transform policies into laws, including a lame Pan African Parliament, weak judicial systems to enforce laws, crude and punitive style of policing and prison services that inhumanely warehouses those considered ‘innocent’ by the very law of the society that imprisons them are the factors that have collectively rendered many of the justice systems, that continually violates the rights of those that in conflict with the law. Institutions like the African Commission are not properly equipped to assist its 55 Member States that are parties to its Charter.

Understanding the Terms &Embracing a Broader Concept of Justice

AU Watch’s Justice program, broadly conceived, is a much broader concept, including programs related to social justice as well.

AU Watch’s work on justice focuses on building accessible, efficient and fair justiceinstitutions that are essential to sustainably reducing poverty and increasing shared prosperity. Strong justice institutions are key to governance and the achievement of the region’s Agenda 2063.

Etannibi E O Alemika describes criminal justice as the norms, processes and decisions pertaining to the enactment and enforcement of criminal laws, the determination of the guilt of crime suspects, and the allocation and administration of punishment and other sanctions. These norms, institutions and processes of criminal justice administration are politically determined, in the sense that their articulation and incorporation into the governance systems of society involve the exercise of political power through the legislative, executive and judicial organs of government.

At the core of the concept of criminal justice are the normative ideas of transgression against criminal code: intention, responsibility or culpability, and desert. The term ‘desert’, which is a central focus of the criminal justice system, refers to what the criminal, victim and society deserve as a consequence of crime. The criminal processes, especially adjudication, are structured to allocate the punishments or corrections deserved by the offender, the restitution due to the victim and society.

At the core of the concept of criminal justice are the normative ideas of transgression against criminal code: intention, responsibility or culpability, and desert. The term ‘desert’, which is a central focus of the criminal justice system, refers to what the criminal, victim and society deserve as a consequence of crime. The criminal processes, especially adjudication, are structured to allocate the punishments or corrections deserved by the offender, the restitution due to the victim and society.

Criminal Justice institutions include courts, prosecutors, public defenders, complaint mechanisms, anti-corruption agencies, ministries of justice, among others. These institutions are the foundation for the social contract between people and the state. They address breaches of law, provide redress for violations of rights, and facilitate peaceful resolution of disputes. They also oversee state institutions and enforce the state’s role as regulator. When justice institutions operate effectively, accountability increases, trust in the government grows, and citizens and businesses can invest with confidence that their property rights will be protected.

What We Do

We work to ensure that Africans are treated fairly by the law, that all of us, including minority and fringe groups that are unable to defend and speak for themselves, have access to the protection of the law — and that the law is moulded, fashioned and used not as an instrument of coercion, but in the service of the people it is supposed to be servicing.

Our (criminal) Justice work include seven key areas of intervention: We Support:

• The African Union and AU Member States to develop regional and national policing and criminal justice systems that treat everyone fairly and equally.

• National justice institutions through targeted interventions that improve the specialist functions of the justice system, as well as its management, governance and oversight; we also support local and civil society organizations that work to improve access to justice generally.

• The AU, its Members and civil society groups who work on social injustice issues like poverty, transnational crimes, corruption and who use the law to seek redress.

• The legal empowerment of women and other minority groupsthrough the strengthening of regional and national regulatory frameworks and institutions.

The Bank adopts a multidisciplinary approach when dealing with justice and development drawing on a wide network of experts, including judges, lawyers, economists, architects and social scientists, as well as specialists in the management of justice sector human resources, finance, infrastructure, data and ICT. In doing so, the Governance GP partners with experts across the Global Practices and the IFC, particularly on issues of commercial law, insolvency and regulatory governance.

The justice work program encompasses the full range of instruments available to the World Bank Group, including investment/project lending, results and policy-based lending, technical assistance, trust funds, grants, partnerships and reimbursable advisory services.

Justice Institutions

The Bank’s efforts to strengthen justice institutions has helped client countries:

• reform legal frameworks for the justice system, including commercial, criminal and procedural codes;

• re-engineer processes to improve work flow efficiency, cut backlogs and reduce opportunities for corruption;

• improve case management systems;

• strengthen human resources and financial management information systems;

• invest in court infrastructure and ICT to improve access, efficiency and transparency, and;

• build capacity through training and peer exchange.

• Supported the establishment and strengthening of specialist judicial institutions, such as commercial courts, anti-corruption courts, and ADR mechanisms, including mediation and arbitration.

World Bank projects in Serbia and Russia contributed to significant reductions in court backlogs, in the time taken to respond to applications and to process cases. In Kenya, the Bank has helped the judiciary to implement a case tracking system and to use its data to drive performance improvement. In Romania, the audio recording of hearings has improved transparency and accountability. In Albania and Colombia, amongst others, judicial reforms have contributed to improvements in court user satisfaction and confidence in justice sector services.

Legal Empowerment

The Bank’s efforts to promote legal empowerment have helped client countries:

• Develop and strengthen legal aid systems, community-based justice and paralegal programs

• Establish and maintain advisory and mediation services

• Conduct legal information and legal literacy campaigns

• Develop legal information websites

• Reform legal education and

• Circulate legal information in lay language

The Bank’s work on legal empowerment typically focuses on poverty-related justice problems such as legal identity, land, displacement, access to basic services and gender-based violence.

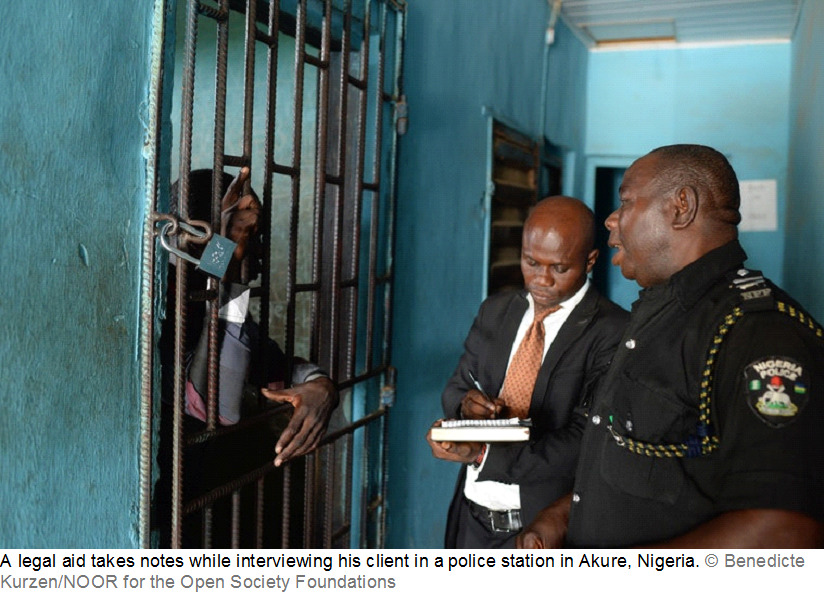

For instance, in Afghanistan the Bank supported an expansion in the number of the legal aid providers. In Nigeria, the Bank helped create legal aid centers. In Bosnia and Herzegovina, the Bank is developing a lay guide for micro and small business owners to help them to navigate justice problems. In the Solomon Islands, the World Bank supported local officers who help communities manage conflicts that undermine security, development and social cohesion.

Justice in Sectors

The Bank’s efforts to strengthen the regulatory frameworks and justice institutions have helped client countries achieve more efficient outcomes not just in the justice sector but also in all sectors that are critical to achieve the World Bank’s twin goals, including health, tax, extractive industries and land administration.

For instance, in Colombia, the Bank helped to develop mechanisms to respond to citizen claims and grievances regarding health care. A project in Pakistan facilitated the litigation of tax cases, thereby helping tackle tax evasion and corruption. In Honduras, the World Bank supported community-based mechanisms to resolve land conflicts. In the Central African Republic the World Bank promoted compliance with the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative. In Cambodia, the Bank supported the Arbitration Council to resolve labor disputes. In Mauritania, a Bank project set up a Financial Intelligence Unit to help fight money laundering. In Sierra Leone, the Bank has supported paralegals to address administrative law issues and improve the delivery of health services.

Analytics and Diagnostics

The Bank’s justice work also includes the publication and dissemination of a variety of justice-related analytics and diagnostics. It undertakes analytic work to understand the challenges facing the justice sector, the institutional framework and the political economy context of reform.

Legal needs surveys, including in Bangladesh, Colombia, Kenya, and Papua New Guinea, have helped understand the justice needs of citizens. Recent Functional Reviews and Institutional and Expenditure Reviews in Serbia, Montenegro, Ukraine and Moldova have informed the reform agenda in those countries and set the baseline for future reform impacts to be measured. The Justice for the Poor program (J4P) has generated analytics on dispute resolution giving a voice to citizens even in challenging contexts of legal pluralism and weak formal institutions. The Doing Business survey includes a Quality of Judicial Process Index that assesses initiatives to improve commercial dispute resolution. Women Business and the Law (WBL) assesses key legal barriers to women’s participation in the economy. The World Bank’s Data and Evidence for Justice Reform (DE JURE) provides a global platform to expand the evidence base of ‘what works’ in justice reform.

Over recent years, many countries had to undertake an in-depth reform to bring their criminal justice system in line with Council of Europe standards. In addition, throughout Europe, criminal justice systems have faced new types of challenges: greater complexity of cases due to societal changes, the development of new technologies and the internationalisation of crime; budgetary constraints; increased workload and at the same growing expectations from the public.

Considering that a fair and efficient criminal justice system is a prerequisite for any democratic society based on the rule of law, the Council of Europe pays a lot of attention to legal and institutional reforms in the sphere of criminal justice.

The Council of Europe has developed a wide range of standards in this area (conventions, recommendations and opinions) and the Human Rights National Implementation Division provides support to member states to improve their implementation at the national level, on the basis of the findings of its monitoring bodies, including the European Court of Human Rights. This support takes the form of legislative expertise on Criminal Codes, Codes of Criminal Procedure, Laws on Prosecution etc., development of regulatory frameworks of prosecution services, support to the development of reform strategies and institutional capacity building for bar associations, prosecution offices and the judiciary.

The Four Universal Principles

The rule of law is a durable system of laws, institutions, norms, and community commitment that delivers:

Accountability

The government as well as private actors are accountable under the law

Just Laws

The laws are clear, publicized, and stable; are applied evenly; and protect fundamental rights, including the security of persons and contract, property, and human rights.

Open Government

Accessible Justice

Justice is delivered timely by competent, ethical, and independent representatives and neutrals who are accessible, have adequate resources, and reflect the makeup of the communities they serve. The processes by which the laws are enacted, administered, and enforced are accessible, fair, and efficient.

These four universal principles constitute a working definition of the rule of law. They were developed in accordance with internationally accepted standards and norms, and were tested and refined in consultation with a wide variety of experts worldwide

Promoting justice to fight impunity for serious crimes (genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, torture, enforced disappearance) contributes to restoring respect for human rights and the rule of law in Africa and to upholding victims’ rights.

AU Watch documents these crimes, assists victims before the courts and advocates for the adoption and implementation of independent procedures and judicial mechanisms.

AU Watch intervenes before the national courts, and in application of extra-territorial or universal jurisdiction, before hybrid tribunals such as the Extraordinary Chambers of the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC) and international courts such as the International Criminal Court (ICC).

An effective criminal justice system is one of the key pillars upon which the concept of the rule of law is built because it serves as a functional mechanism to redress grievances and bring violators of social norms to justice, and how well a country manages its criminal justice system affects its overall performance on the governance index. Unfortunately, many of Africa’s criminal justice system are fundamentally flawed and the defects manifest at every processing point on the entire criminal justice system line.