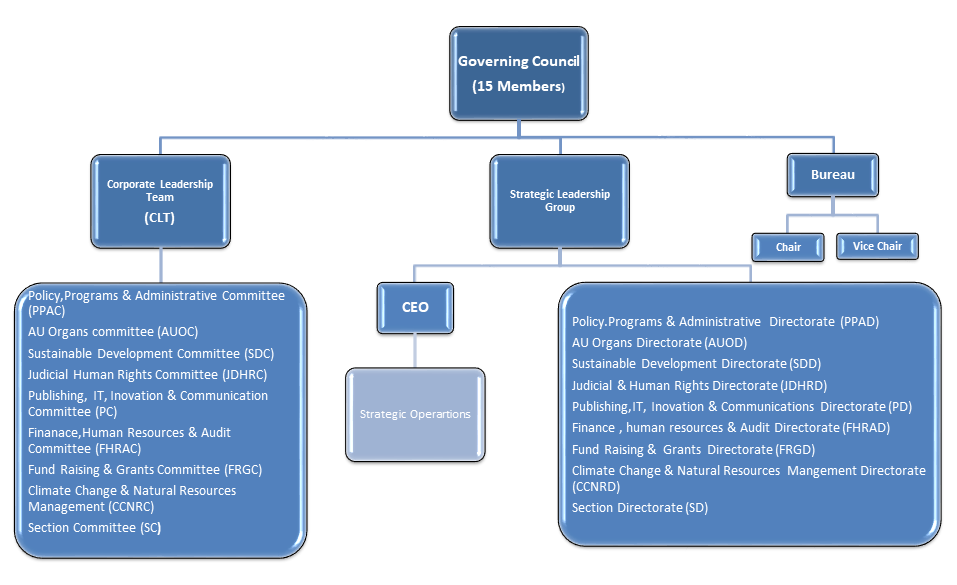

Governance responsibilities, including management of the strategy and implementation of AU Watch worldwide work reside with the Governing Council led by its Chairperson, and assisted by the Strategic Leadership Group (who are all staff members) and the Corporate Leadership Team.

Chairperson

Bahame Tom Mukirya Nyanduga

We believe that great ideas and strong institutions can promote a better world

AU Watch is accountable to a fifteen-person Governing Council as laid out in its constitution. Governance responsibilities for the operation and management of AU Watch reside fully with the Governing Council led by its Chairperson and assisted by the Strategic Leadership Group (SLG) and the Corporate Leadership Team (CLT). The Governing Council provides intellectual guidance on the broad scope of AU Watch’s activities, provides oversight and governance of the organisation’s financial stability and executive leadership. It is also responsible for agreeing on an overall strategy, setting policy, monitoring performance and promoting the interests of AU Watch. The composition of AU Watch’s Governing Council takes into consideration sub-regional representation and consists of a Chairperson, Vice-Chair, a Treasurer and other directors who are leaders in their fields of operation. The SLG and the Policy, Programs, and Administrative Committee implements the organisation’s strategic plan and direct all aspects of its program and operational activities.

The Governing Council includes two staff members, with none voting rights, one of which is the CEO & Executive Director and Head of AU Watch and AU Watch’s Director of Strategic Operations.

The Governing Council is also assisted by ten sub-committees and by the Strategic Leadership Group (SLG), who are all staff members. The Strategic Leadership Group (SLG), the Senior Management Team (SMT) of AU Watch, is the executive decision-making body of AU Watch. It is an eleven-person body, headed by the President and CEO and directly assisted by AU Watch’s Director of Strategic Operations. The other nine members are the heads of the various Directorates. Its function is to manage AU Watch, implement the policies of the Governing Council and take strategic decisions.

The Governing Council and the SLG are supported by ten advisory Sub-committees (Corporate Leadership Team) that look at specific issues in the areas of policies, programs, risk management, research strategy, ICT, media, education, campaigns and advocacy, development, resources, finance, and fundraising. The five-person Corporate Leadership Team, generally, has direct policy oversight over its corresponding Directorate.

WE ARE AU WATCH AND WE MEAN BUSINESS. COME JOIN US AND LET’S CREATE THE AFRICA WE ALL WANT! COME JOIN US AND LET US MAKE 203 A REALITY, IF NOT FOR OURSELVES, BUT FOR OUR CHILDREN!

How can you help us? See our vacancy notices

Like other human rights systems, the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights establishes the absolute prohibition of torture, cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment. Article 5 of the Charter provides that “every individual shall have the right to the respect of the dignity inherent in a human being and to the recognition of his legal status. All forms of exploitation and degradation of man, particularly slavery, slave trade, torture, cruel, inhuman or degrading punishment and treatment shall be prohibited.” The Charter also establishes a regional human rights body, the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights, with the mandate to promote respect for the Charter, ensure the protection of the rights and fundamental freedoms contained therein, and make recommendations for its application. To fulfill its mission, the African Commission works with different partners, which include States Parties to the African Charter, national human rights institutions and non-governmental organizations (NGOs).

It is in this context of cooperation that AU Watch is undertaking an Africa-wide project to:

Why Media and Outreach Services Promote and Protect Human Rights?

As with other regional human rights systems, the African human rights system is composed of four pillars:

The overall political and institutional framework for the promotion of democracy, governance and human rights in Africa is the African Governance Architecture, established during the 16thOrdinary Session of the AU Assembly of Heads of State and Government in 2011. The AGA is composed of three principal pillars: (i) norms; (ii) organs and institutions and (iii) oversight mechanisms.

The Roadmap to the Joint Africa-EU Strategy approved in April 2014by African and European Heads of State and Government identifies democracy, good governance and the defence and protection of human rights on both continents as a priority.

This Media Strategy will mainly focus on the AU organs with a human rights mandate

Lack of Political Will:

There are also political institutions not totally independent from the AUMS. 1. Lack of political will: the AUMS have an ambivalent relationship with the African human rights system. On one hand, they would like to strengthen it as part of their strategy of finding “African solutions to African problems”. On the other they do not provide it with sufficient resources and try to interfere with the system in order to avoid being criticized by its supervisory bodies. This lack of political support is also one of the key reasons for the limited amount of compliance with the decisions issued by the Commission and the little margin of manoeuvre of the Court. Also, the content of the human rights instruments are a reflection of the political will of African countries at the time of the adoption, and some provisions or lack thereof are hampering litigation with the institutions4. There are also political institutions not totally independent from the AUMS.

Lack of Universality: the process of ratification by States Parties is very slow and several key instruments have not yet been ratified (or domesticated) by even half of the AUMS. Only seven AUMS have ratified all the main governance and human rights instruments. Only the Commission can be considered a truly continental instrument with 53 ratifications out of 54. The fact that only 28 countries have ratified the Protocol of the African Court and only 7 countries have signed the special declaration allowing individuals and NGOs to seize the Court seriously undermines access to the system.[1] Being ratified by 47 Member States, the African Children’s Charter seems to be placed in better position. However the fact that 7 countries are yet to ratify and the number of reservations placed against the application of some of the key provisions of the Charter undermines its universal application in the continent. The African Charter on Democracy, Elections and Governance entered into force 2½ years ago and has 23 ratifications. The recent new protocol of the PAP giving some legislative power has not been ratified so far by any AUMS. The main reasons for the slow and incomplete ratification process are weak linkages between the system and national bodies (e.g. parliaments, judiciaries), lack of political will, and insufficient knowledge about the system.

Lack of Knowledge About the AU and the Human Rights Organs: Very few Africans know what the AU is doing. For hundreds of millions of Africans citizens it is an opaque, non-transparent organization which is not fit for purpose. A scientific study carried out by AU Watch in 2014 showed that over 98n percent of the people polled had no idea what the AU human rights organs are.

Lack of Human Resource Capacity: All the AU human rights organs have very weak secretariats. In the case of the Child Committee, it does not have one of its own. They have insufficient qualified manpower, including for the support to the special mechanisms/rapporteurs. This significantly constrains the capacities of the secretariats to fulfil their roles including not being sufficiently responsive to CSOs’ requests, communications, etc. This also constrains the synergies that need to be created between the different organs to improve the working of the regional human rights system (e.g. transmission of cases from the Commission to the Court, in the future, also from the Child Committee to the Court).

Lack of Financial Resources: States Parties provide insufficient resources. However, it is also worth noting that the resources received are probably not used in the most effective way (lack of result oriented action plans). The African Union, shamelessly takes money from anyone who is ready to give them money, even though its Member states can easily afford it. The European Union collectively (EU and its Member States) is the biggest contributor to the African Union, supporting more than 80% of the African Union Commission (AUC) programme budget.

The European Commission alone has provided approx. EUR 1.6 billion to the African Union since 2003. In 2014, the Commission contracted for 424 million Euros with the AU. Cooperation between EU and AU covers mainly peace and security operations, capacity building activities as well as cooperation programmes in different relevant policy areas for Africa, involving a large variety of different actors such as Member States, Institutions and implementing partners.

[1]Rwanda has withdrawn its consent.

This project was borne out of the need to explain the pervasive poverty in Africa’s mostly patrimonial. Whilst AU Watch recognizes the matrix of reasons that keep Africa poor, we agree with Geraldine Bedell (2009) of The Guardian newspaper who wrote that “amount of aid, debt relief or trade is going to make a difference until the problems of corruption are solved: “Corruption is problem number one, two and three on that continent.”On the particular issue of corruption, one of the arguments made by AU Watch is that the continuous accretion of state power and authority dramatized under Africa’s confusing and contradicting political systems state was a logical extension of the neo-patrimonial state, where state managers are only interested in mobilising and controlling resources for personal rather than national resources. Corruption unfortunately has become more entrenched. The thieves have become bolder. A 2002 AU study estimated that corruption cost the continent roughly $150 billion a year. It is feared that in 2016 it could be over $170 billion. Yet in that same period it received $22.5 billion in aid from developed countries. Honestly, step back and repeat slowly $150 billion! Do we really need complex economic and political explanations that why we are wallowing in the mire of poverty? Have we not made our problems worse?