Pan Africanism

Issues and Trends in Contemporary African Politics: Stability, Development, and Democratization

By George Akeya Agbango

Summary

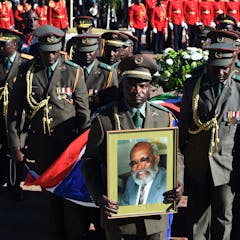

Africa, at the close of the twentieth century, has witnessed a tremendous amount of social, economic, & political transformation. By tackling the issues of political instability, democratization, & economic development, this book goes to the heart of the African conundrum & makes an invaluable contribution to Africa’s development. Written by Africans, it offers a much needed <> that is often lacking in most development literature. African authors are not so encumbered by <> or <> & can write more candidly on events as they see them. The book constitutes a long-awaited break with orthodoxy & makes a pioneering effort to tackle issues traditionally spurned by experts because of their rigid separation of economic development & politics. The writers offer constructive solutions to Africa’s problems – solutions which only Africans would dare to suggest. Contents: George A. Agbango: Political Instability & Economic Development in Sub-Saharan Africa – Nchor B. Okorn: Violence: The Perennial Obstacle to Social, Economic & Political Development in Nigeria 1960-1990 – George A. Agbango: The Crises of Nation Building: The Liberian Experience – Julius O. Ihonvbere: Election Monitoring & the Democratization Agenda in Africa: The Case of the 1991 Zambian Elections – Baffour Agyeman-Duah: Global Transformation & Political Reforms in Africa: The Case of Ghana – Yakubu Saaka: Legitimizing the Illegitimate: The 1992 Presidential Election as a Prelude to Ghana’s Fourth Republic – Henry A. Elonge: Visions of Change in Cameroon Within the Context of a New World Order – Walle Engedayehu: Ethiopia: The Pitfalls of Ethnic Federalism – Margaret C. Lee: South Africa: The Long & Arduous Road to a New Dispensation – Akwasi Osei: South Africa in the African Dilemma – Julius O. Ihonvbere: Democratization in Africa: Challenges & Prospects – George Ayittey: Obstacles to African Development – Julius O. Ihonvbere: Pan-Africanism: Agenda for African Unity in the 1990’s?

The Urban Plantation: Racism & Colonialism in the Post Civil Rights Era

By Robert Staples

Excerpt

In the post-slavery years various theoretical perspectives have competed as an explanation of the status of Afro-Americans in the United States. Until the last 20 years those theories were all in the range of biological determinism to racial equality through assimilation. While Pan-Africanism took hold as a social movement during certain early periods, it never fitted into the mainstream of scholarly thought about the condition or fate of Afro-Americans until recent years. After assimilation concepts were put to a reality test by the civil rights movement during the 1960’s and found wanting, a more nationalist orientation emerged among black intellectuals in the late ’60’s. Along with a renaissance of Marxist theory, the theoretical perspective that began to dominate the scholarly interpretation of black life was internal colonialism.

This transformation in theory and ideology arose because blacks began to define the nature of their situation, to write their own books and publish through black-controlled media. Members of the liberal sociological establishment either retained their faith in assimilation as a solution to the race problem, retreated from the study of race relations or in a few cases became part of an intellectual neo-conservative white backlash. As conceptual models Pan-Africanism and Marxism seemed more relevant to the black reality. Pan-Africanism filled the need to link up the cultural unity and common struggle of peoples of African descent while Marxism stressed the class exploitation of the black population. Both models, however, have limited visions of black life. As William Strickland has noted, “The Pan-Africanists seemed to want to substitute the African reality for the American while the Marxists appeared . . .

Pan-Africanism Reconsidered

By American Society of African Culture

Excerpt

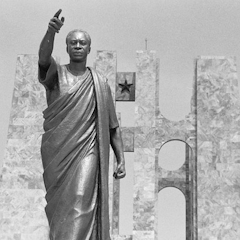

It was on the eve of a critical phase of African liberation — the formation of the Republic of the Congo — that the Third Annual Conference of the American Society of African Culture was held in Philadelphia at the University of Pennsylvania in June, 1960. The sessions took place in historic Houston Hall — the same setting where, at the beginning of World War II, Kwame Nkrumah, then a teaching fellow at the university, had shared the platform with Justice William H. Hastie, Congressman Adam Clayton Powell, and AMSAC’s Executive Director, John A. Davis, to consider the subject of African freedom. Alioune Diop, the Senegalese Secretary General and founder of the parent organization, the Société Africaine de Culture, could not remain after the Philadelphia sessions for the tour of American cities with other African visitors because of his scheduled flight to attend what proved to be that crucial event in African resurgence, the inauguration of the Republic of the Congo. In a sense, the Belgian Congo experience — or, more precisely, what at the time of writing still threatens to be the Belgian Congo disaster — reflects in microcosm the clash of forces inherent in the theme of the conference, “African Unities and Pan-Africanism.” The divisive aspect of nationalism is there, threatening to splinter the Congo hopelessly into its several constituent parts; and the influence of an embattled Pan-Africanism is also manifest even in secessionist Katanga in demonstrations supporting the Republic.

Pan-Africanism is a timely subject. It has been the rallying slogan, the springboard, the ideological vehicle for the common efforts of exiled Africans, West Indians, and American Negroes to advance the cause of Africa and of Africans. But Pan-Africanism, like Joseph’s coat, is described in many colors; at no time have these variegated hues been more significant than now. These are the years — 1960 is in a large measure the year — of Africa’s liberation. The drive toward freedom has, or shortly will have, succeeded, with certain reluctant exceptions at the extreme ends of the continent. That very success has, in large degree, automatically eliminated this source of psychological energy, of unity and effort, generated in the struggle against France, England . . .

The Struggles of John Brown Russwurm: The Life and Writings of a Pan-Africanist Pioneer, 1799-1851

By Winston James

Synopsis

“If I know my own heart, I can truly say, that I have not a selfish wish in placing myself under the patronage of the [American Colonization] Society; usefulness in my day and generation, is what I principally court.”

“Sensible then, as all are of the disadvantages under which we at present labour, can any consider it a mark of folly, for us to cast our eyes upon some other portion of the globe where all these inconveniences are removed where the Man of Colour freed from the fetters and prejudice, and degradation, under which he labours in this land, may walk forth in all the majesty of his creation- a new born creature- a Free Man!”

– John Brown Russwurm, 1829.

John Brown Russwurm (1799-1851) is almost completely missing from the annals of the Pan-African movement, despite the pioneering role he played as an educator, abolitionist, editor, government official, emigrationist and colonizationist. Russwurm’s life is one of “firsts”: first African American graduate of Maine’s Bowdoin College; co-founder of Freedom’s Journal, America’s first newspaper to be owned, operated, and edited by African Americans; and, following his emigration to Africa, first black governor of the Maryland section of Liberia. Despite his accomplishments, Russwurm struggled internally with the perennial Pan-Africanist dilemma of whether to go to Africa or stay and fight in the United States, and his ordeal was the first of its kind to be experienced and resolved before the public eye.

Pan-Africanism and East African integration

By Joseph S. Nye Jr

Excerpt

One of the most interesting developments in international politics since the end of the Second World War has been the attempt to integrate the sovereign states of Europe into some form of larger unity. It is not surprising that both scholars and statesmen from other areas of the world have begun to make generalizations about regional integration based largely on the European experience.

Thus far we have too few cases of regional integration to develop a satisfactory comparative study. We are not sure how the process of becoming more interdependent in social and economic affairs relates to unification, the process of forming a larger political union. We do not know whether there is enough similarity between regional integration among industrial states and among developing countries to allow us to explain the process in both contexts with the same theory. For example, current theory regarding European integration assigns ideology a minimal role. Yet most Africans who are interested in regional integration of their continent are committed to Pan-Africanism, an ideology of unity.

This book is not about Pan-Africanism in the sense that it is concerned with its lengthy history or varying content in different parts of Africa. It is rather an attempt to evaluate the impact of a system of ideas that East Africans call PanAfricanism upon a particular case of integration and attempted unification. Can we understand regional integration in Africa on the basis of our “European theories,” or must we adapt those theories to take ideological rhetoric into account?

Africa: Social Problems of Change and Conflict

By Pierre L. Van Den Berghe

Excerpt

Pierre L. van den Berghe

To say that the present collection of essays fills a gap in Africanist scholarship is perhaps an overstatement, since all of them have already been printed elsewhere. The papers contained herein do nevertheless highlight a new look at the continent, and put known facts in a different perspective.

From the late nineteenth century until fairly recently, much of subSaharan Africanist scholarship shared, albeit in more sophisticated, subtle and disguised form, what might be termed the “colonial ethos.” In few cases has the impingement of ideology on social science research been as blatant. The situation is hardly surprising, since scholars from the colonial powers nearly monopolized the field, and since many of them even were direct or indirect participants in the colonial systenm (e.g., administrators, missionaries, technical advisers, and the like). To be sure, many social scientists rejected the racist mythology of white superiority, but the majority implicitly accepted a number of ethnocentric postulates which made them look at black Africans as a very different kind of people, and made them adopt particularistic criteria and concepts in dealing with their subject matter. Only recently are we experiencing the explosion of the myths of Africa as a primitive, unchanging, ahistorical, isolated continent, fragmented into a multiplicity of self-contained, mutually antagonistic, but internally stable and harmonious “tribes.”

Africa: The Politics of Independence and Unity

By Immanuel Wallerstein

Synopsis

Africa: The Politics of Independence and Unity combines into one edition for the first time Africa: The Politics of Independence and Africa: The Politics of Unity. With a new introduction by the author, this edition provides some of the earliest and most valuable analysis of African politics during the period when the colonial system began to disintegrate. The influential Africa: The Politics of Independence was written as Africa was just realizing independence and still reveling in the optimism it brought. Immanuel Wallerstein was one of the few scholars who had traveled throughout Africa during the collapse of colonial rule. As a result, his interpretive essay captures the dynamism of that period of transformation and adroitly analyzes Africa’s modern political developments during the nascent process of decolonization. Africa: The Politics of Unity, published six years later, examines the African unity movement that arose between 1957 and 1965 and its revolutionary core. It is often considered the first thorough analysis of the postindependence history of Africa.

The Resurgence of Race: Black Social Theory from Reconstruction to the Pan-African Conferences

By William Toll

Excerpt

In 1903 W. E. B. DuBois published the most influential collection of essays ever written by a Black American, The Souls of Black Folk. The book ranged over many social, historical, and literary topics, but its most profound theme was the exposition of a distinct Black psychology. Blacks, DuBois argued, had the same hopes and desires as other peoples, but they had been treated as strangers in their own land. Subject to enslavement rather than free migration and to stigma rather than equal opportunity, they had been “born with a veil” and perceived the world through a maze of stereotypes imposed on them by white America. His essays, DuBois hoped, would reveal the human feelings and unique achievements of Blacks and demonstrate how they confronted their inner doubts. The Souls of Black Folk not only reflected the influence of DuBois’s education at Harvard and Berlin, but also the intensive and growing debate among Blacks over their history and destiny. America produced the first stratum of Western educated Black intellectuals who reflected on the problems of colonial control and proposed various theories and strategies to combat it. Two dominant images of the freedmen emerged from their debates. The first, suggested by former slaves like Frederick Douglass and developed by T. Thomas Fortune and Booker T. Washington, depicted the freedmen as an impoverished peasantry in . . .

W. E. B. Du Bois and American Political Thought: Fabianism and the Color Line

By Adolph L. Reed Jr

Synopsis

In this explosive book, Adolph Reed covers for the first time the full sweep and totality of W. E. B. Du Bois’s political thought. Departing from existing scholarship, Reed locates the sources of Du Bois’s thought in the cauldron of reform-minded intellectual life at the turn of the century, demonstrating that a commitment to liberal collectivism, an essentially Fabian socialism, remained pivotal in Du Bois’s thought even as he embraced a range of political programs over time, including radical Marxism. He remaps the history of twentieth-century progressive thought and sharply criticizing recent trends in Afro-American, literary, and cultural studies.

W. E. B. Du Bois, Marcus Garvey, and Pan-Africanism in Liberia, 1919-1924

By M’bayo, Tamba E

Article excerpt

PAN-AFRICANISM–the perceived need to mobilize all peoples of African descent against racism and colonialism–was perhaps one of the most enduring responses to the legacy of European slavery and imperialism. Although a project centered around the notion of Africa, however, Pan-Africanism was in fact heavily influenced by Western discourses on Africa and Africans. It was this Western understanding that profoundly affected the thinking of Africans in diaspora, and that in turn sometimes engendered conflicting thoughts and attitudes toward issues of race, identity, and nationality. (1) Pan-Africanism sought to unite all people of African descent and thereby demonstrate the mutual bond believed to exist among blacks regardless of geographic location. In reality, African American and Afro-Caribbean Pan-Africanists often adopted contradictory positions that belied their universalist Pan-Africanist aspirations. Indeed, despite its rhetoric and noble ideals, inconsistencies between Pan-African theory and practice have been integral parts of the movement’s long and checkered history. This study analyzes these inconsistencies and indeed the larger paradoxes and problems of Pan-Africanism. It does so by analyzing the separate encounters of U.S.-born William E. Burghardt Du Bois and the Jamaican-born Marcus Garvey with the West African republic of Liberia between 1919 and 1924, as each black leader attempted to launch his own particular strand of Pan-Africanism in Africa. (2)

Mark Nartey, Hong Kong Polytechnic University

John J Stremlau, University of the Witwatersrand

Akwasi Kwarteng Amoako-Gyampah, University of Education

Gwen Ansell, University of Pretoria

Dan Hodgkinson, University of Oxford and Luke Melchiorre, Universidad de los Andes

Cheryl Hendricks, Human Sciences Research Council and Keith Gottschalk, University of the Western Cape

Femi Amao, University of Sussex

Frank Mattheis, University of Pretoria and John Kotsopoulos, University of Pretoria

Edward Webster, University of the Witwatersrand

Heike Becker, University of the Western Cape

Uchenna Okeja, Rhodes University

Michèle Olivier, University of Hull

Edward Webster, University of the Witwatersrand

Abdul-Jalilu Ateku, University of Nottingham

Frank Mattheis, University of Pretoria

Hopeton Dunn, University of the West Indies, Mona Campus

Suraj Yengde, Harvard University

Mark Swilling, Stellenbosch University

David Everatt, University of the Witwatersrand

Mashupye Herbert Maserumule, Tshwane University of Technology